Saturday Newsletter: NOAA Updates Their Outlook for February on January 31, 2025

More Thoughts On How Weather Affected the Los Angeles Fires

PART I

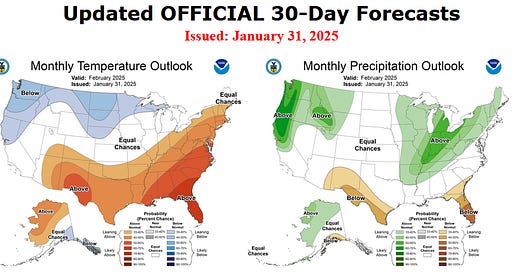

At the end of every month, NOAA updates its Outlook for the following month which in this case is February of 2025. We are reporting on that tonight. In this article, I refer to February 2025 as "The New Month".

There have not been significant changes in the Outlook for the new month compared to the Mid-Month Outlook for February.

Changes made are addressed in the NOAA Discussion so it is well worth reading. We provided the prior Mid-Month Outlook for the new month for comparison. It is easy to see substantial changes made to the weather outlook by comparing the Mid-Month and Updated Maps.

The article includes the Drought Outlook for the new month. NOAA also adjusted the previously issued three-month Drought Outlook to reflect any changes in the new month's Drought Outlook. We also provide the Week 2/3 Tropical Outlook for the World. The Tropical Outlet includes both direct and indirect potential impacts to the Southern Tier of CONUS. We also include links to a whole set of forecasts for parts of the new month. These are both useful and provide a crosscheck on the validity of the new month's Outlook. The whole should be equal to the sum of its parts.

The best way to understand the updated outlook for the new month is to view the maps and read the NOAA discussion. I have highlighted the key statements in the NOAA Discussion.

I am going to start with graphics that show the updated Outlook for the new month and the earlier Mid-Month Outlook for the new month. This is followed by a graphic that shows both the Updated Outlook for the new month and the previously issued three-month outlook for the three-month period. So you get the full picture in three graphics.

Here is the updated Outlook for February 2025.

For Comparison Purposes, Here is the earlier Mid-Month Outlook for January, 2025

It is important to remember that the maps show deviations from the current definition of normal which is the period 1991 through 2020. So this is not a forecast of the absolute value of temperature or precipitation but the change from what is defined as normal or to use the technical term climatology.

There is very little change from the Mid-Month outlook issued 15 days ago. This then gives us increased confidence in the January 16, 2025 three-month FMA temperature and precipitation Outlooks which are shown in the following graphic. If there had been major changes to the Mid-Month Outlook for the Next Month, we would have to consider if the three-month Outlook issued at that time was still valid.

NOAA provided a combination of the Updated Outlook for the New Month and the Three-Month Outlook.

The top pair of maps are again the Updated Outlook for the new month. There is a temperature map and a precipitation map. The bottom row shows the previously issued three-month outlooks which includes the new month. I think the outlook maps are self-explanatory.

The basic information for February is shown above. There is a lot more information in Part II of this article.

Part II

Here are larger versions of the February Temperature and Precipitation Outlook maps.

NOAA (Really the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Division CPC) Discussion. I have shown certain important points in bold type. My comments if any are in brackets [ ].

30-DAY OUTLOOK DISCUSSION FOR FEBRUARY 2025

The updated monthly temperature and precipitation outlooks for February 2025 are based primarily on WPC’s Week-1 temperature and precipitation forecasts, two-week GEFS and European Prediction System (EPS) ensemble mean temperature and precipitation dynamical forecasts, CPC’s Week-2 and Weeks 3-4 temperature and precipitation outlooks, subseasonal GEFS/CFSv2 guidance, the most recent runs of the monthly CFSv2 temperature and precipitation forecasts, and on weak La Niña composites. In addition, the latest information regarding the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), snow cover, Great Lakes ice coverage, and the latest 30-day temperature and precipitation observations were also considered.

The updated temperature outlook for February 2025 calls for increased chances of below normal temperatures over southeastern Alaska, and from the Pacific Northwest and the northern half of California eastward across portions of the Intermountain region and far northern Rockies, the northern third of the Great Plains, northern portions of Minnesota and Wisconsin, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. This is based on a subjective consensus of the various official outlooks and model runs noted earlier that comprise the monthly time period. Above normal temperature chances are elevated for much of the southern and eastern contiguous U.S. (CONUS). Maximum probabilities of 60-70% are depicted over Florida and portions of Georgia and South Carolina. In the eastern CONUS, this is consistent with MJO lagged temperature composites with the enhanced convective phase propagating through the Maritime Continent region. However, it is noted that the composites also show a trend towards colder temperatures in the East towards the end of February. The widespread coverage of favored above normal temperatures across much of the CONUS is supported by historical La Niña composites, the CFSv2, and the subseasonal GEFS-CFSv2 temperature guidance. Above normal temperatures are also favored over approximately the northern and western halves of Mainland Alaska, based on GEFS and EPS 2-meter temperature anomalies through the first half of February, the CFSv2 model, and GEFS-CFSv2 subseasonal temperature guidance. Equal Chances (EC) of below, near, and above normal temperatures are favored for remaining areas where models and tools displayed weak and/or conflicting signals.

The updated precipitation outlook for February 2025 depicts increased chances of above normal precipitation from northern and central California and the Pacific Northwest eastward across the northern Intermountain region to eastern Montana. Maximum probabilities of 60-70% are indicated for the Coastal Ranges and Cas cades of the Pacific Northwest, extending southward across the Klamath range and northern and central Sierras of California. This broad pattern of favored above normal precipitation is generally consistent with historical La Niña precipitation composites. For the West Coast area, anywhere from 3-8+ inches of precipitation (liquid equivalent) is predicted to fall within the first week of February associated with atmospheric river activity. Chances favoring above normal precipitation are also elevated across most of the Mississippi Valley, the Great Lakes region, Ohio and Tennessee Valleys, most of the Appalachians, and interior portions of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. Maximum probabilities of 50-60% are depicted from the vicinity of the Mississippi-Ohio River Confluence northeastward across most of the eastern half of the Great Lakes region. This is consistent with much of the objective model guidance and La Niña composites, and denotes the expected location of the mean storm track. Odds favoring below normal precipitation are enhanced for eastern Arizona, most of New Mexico, western and southern portions of Texas, and much of the Southern Atlantic region. These favored areas of relative dryness are commonly observed during La Niña winters, though the indicated spatial coverage of below normal precipitation is significantly reduced relative to moderate or strong La Niña composites. Maximum odds of 50-60% favoring below normal precipitation are indicated over southern Florida. For Alaska, a combination of dynamical model guidance and La Niña composites slightly favors above normal precipitation chances over northern, central, and western Mainland Alaska, continuing southwestward across much of the Aleutians, and below normal precipitation chances over parts of southcentral and southeastern Mainland Alaska. Equal Chances (EC) of below, near, and above normal precipitation is favored for remaining areas where models and tools displayed weak and/or conflicting signals .

Drought Outlook

Here is the newly issued Drought Outlook for the month.

You can see where drought development or persistence is likely. The summary and detailed discussions that accompany this graphic can be accessed HERE, but the short version is shown below.

Here is the short version of the drought summary

Latest Monthly Assessment - During the past 4 weeks, widespread precipitation deficits were observed across much of the lower 48 states. A 1 to 2 class drought degradation was seen in the Mid-Atlantic, Southwest, and southern California, with drought expansion across southwestern quarter of the contiguous United States as of the January 28, 2025 US Drought Monitor. However, periodic precipitation across the Pacific Northwest, Rockies, and parts of the eastern half of the U.S. brought 1 to 2 class drought amelioration. With La Nina conditions continue to be favored in the February period, the CPC monthly outlooks favor a canonical La Nina response pattern, with drier and warmer conditions across the southern tier of the CONUS, a winter storm track favoring the Great Lakes, Tennessee-Ohio Valleys, and interior New England, and an enhanced wet month for the Northwest. Therefore, drought reduction is favored across parts of the Northwest, Midwest, Tennessee Valley, and Northeast. Across the southern tier, drought persistence or expansion is expected for portions of Arizona, New Mexico, southern and western Texas, and the Southeast.

During the past few weeks the existing drought and abnormal dry conditions vary across much of the Hawaii Islands. February is a climatological wet season for the Islands with the La Nina conditions typically favoring enhanced rainfall across the region, drought reduction is likely for February. No drought conditions are currently present or favored to develop across Alaska, Puerto Rico, or the US Virgin Islands.

We also have an updated Seasonal Drought Outlook (link).

This three-month outlook forecast is a combination of the mid-month three-month drought forecast and the revised drought forecast for February.

The Tropical Forecast can Impact the Outlook in ways not reflected in the NOAA discussion. This shows the Weeks 2 and 3 Outlooks.

I do not see anything here that is very significant for the U.S. but there is a lot that is significant for other parts of the World. To update this forecast (which updates on Tuesdays), click HERE

It is useful to review the prior month.

Month-to-date Temperature for the prior month can be found below. As we head into the new month, the month to date Temperature can be found HERE

Month-to-date Precipitation for the prior month can be found below. As we head into the new month, the month to date Temperature can be found HERE

It looks a lot like a La Nina pattern.

I hope you found this article interesting and useful

Sponsored Content:

Porter Stansberry: These are Trump's 10 Secret Stocks

Ten investments secretly owned by Trump's biggest backers.

Ten investments intrinsically tied to the policies Trump will put in place.

Ten investments with the potential to return 10x or more... but only if you act right now.

Go here to find out the names of these ten stocks.

ref: 5941

The EconCurrents is primarily a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

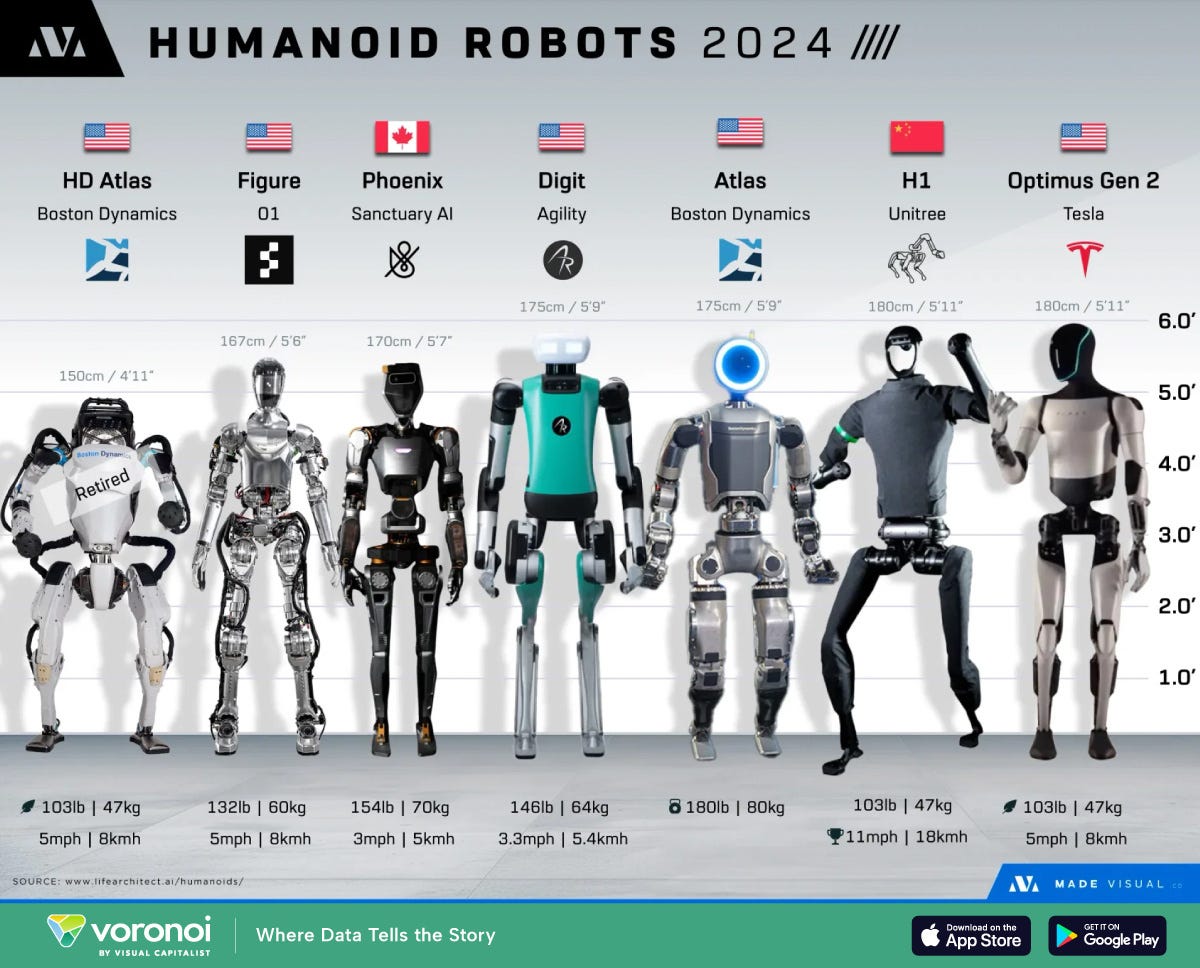

Infographic of the Day from Visual Capitalist:

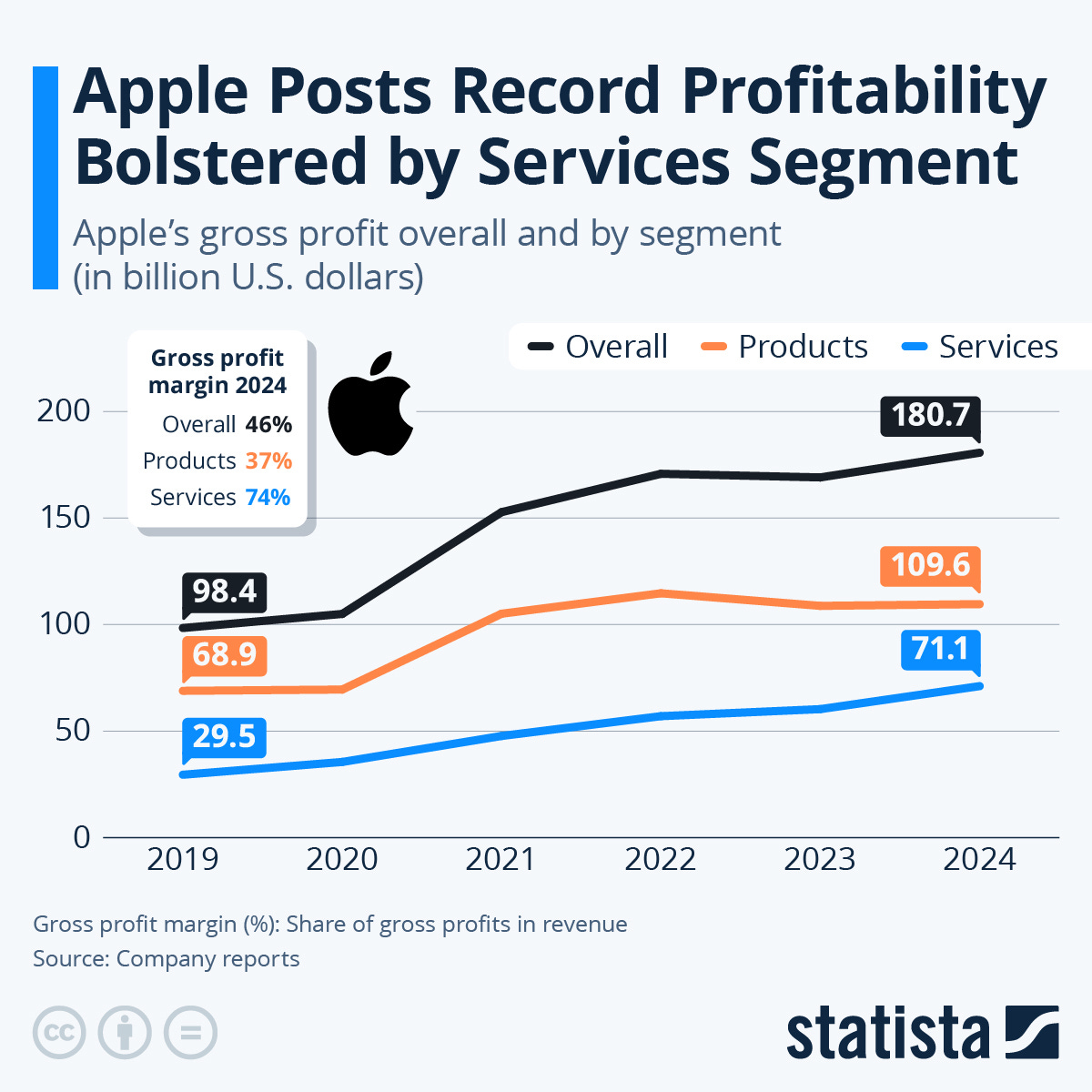

Statista Graphic of the Day:

You will find more infographics at Statista

Other Posts We Are Reading:

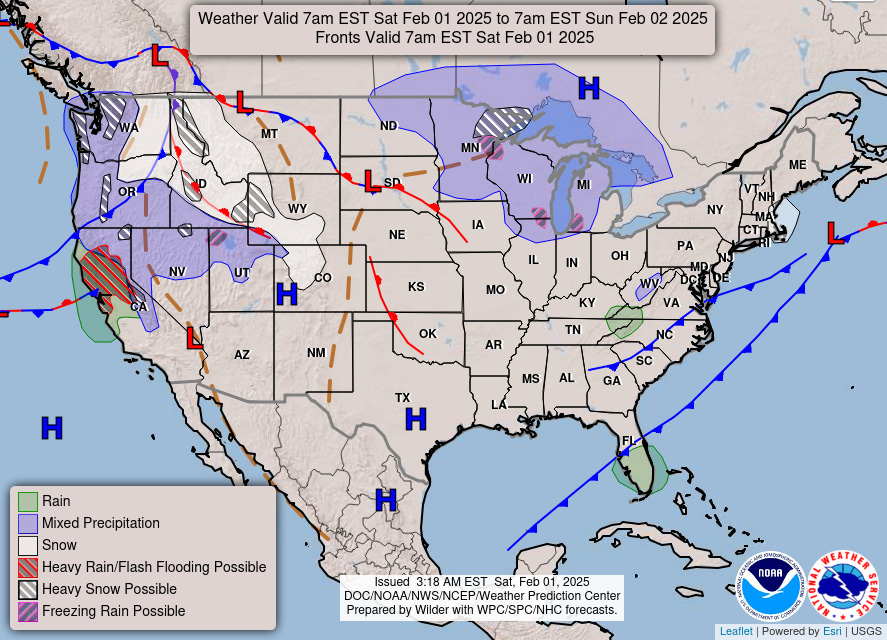

Weather Outlook for the U.S. for Today Through at Least 22 Days and a Six-Day Forecast for the World: – Posted on February 1, 2025

This article focuses on what we are paying attention to in the next 48 to 72 hours. The article also includes weather maps for longer-term U.S. outlooks (up to four weeks) and a six-day World weather outlook which can be very useful for travelers.

Climate change increased the likelihood of wildfire disaster in highly exposed Los Angeles area

Main Findings:

Coastal Southern California is an environment highly prone to catastrophic wildfires. The destructiveness of a fire thus also strongly depends not only on the weather conditions but also on whether land use and fire management strategies take these characteristics into account. The Palisades Fire occurred in an officially designated Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone, while the Eaton Fire was only partly within such an area. This means fire risk has always been very high and building regulations require at least 200 ft of vegetation management around structures within the designated Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zones. Post-fire assessments will check compliance with these requirements.

Looking at weather observations, in today’s climate with 1.3°C global warming relative to preindustrial, the extreme Fire Weather Index (FWI) conditions that drove the LA fires are expected to occur on average once in 17 years. Compared to a 1.3°C cooler climate this is an increase in likelihood of about 35% and an increase in the intensity of the FWI of about 6%. This trend is however not linear, with high FWI conditions increasing faster in recent decades.

To determine the role of climate change in this observed trend we combine the observation-based estimates with climate models. Eight of the eleven models examined also show an increase in extreme January FWI, increasing our confidence that climate change is driving this trend. Combining models and observations, we find that human-induced warming from burning fossil fuels made the peak January FWI more intense, with an estimated 6% increase in intensity, and 35% more probable. Fire weather indices consist of many variables, which are not always well represented by climate models. Wind, in particular, is often poorly represented. While we have high confidence in the qualitative change, that the likelihood and intensity of the FWI has increased due to human-induced climate change, the precise numbers have a wide range of uncertainty due to the model performance.

This trend is projected to continue into the future, with peak FWI intensifying by a further 3% and similar values becoming a further 35% more likely if the world warms to 2.6°C, which is the lowest warming expected under current policies by 2100.

We also assess the drought conditions leading up to the fires, using two different indices. First, we consider the October-December (OND) standardised precipitation index, which is defined relative to the 1991-2020 climatology and measures how dry OND 2024 was in comparison. We calculated the index for today’s climate of 2024 and a 1.3° colder climate. Similarly dry seasons are expected to occur on average once every 20 years in the current climate; this is 2.4 times more likely than in a preindustrial climate. The OND ENSO conditions also increased the likelihood of the drought by a factor of 1.8 relative to neutral ENSO conditions. Climate models do not agree on the direction of precipitation trends in this region, so we are unable to formally attribute this change to global warming.

We further assess changes in the timing of the end of the dry season. Analysing observations, we find that the length of the dry season has increased by about 23 days since the global climate was 1.3°C cooler. This means that, due to the burning of fossil fuels, the dry season, when a lot of fuel is available, and the Santa Ana winds, that are crucial for the initial spread of wildfires, are increasingly overlapping.

Our observational analysis shows that the frequency of an atmospheric circulation pattern such as that of January 8th 2025, which is known to strengthen Santa Ana wind events, has increased in winter, raising the risk of weather conditions that drive the spread of wildfire. Whether this trend is attributable to human-caused climate change requires a more in depth study of the patterns in observations and climate models.

As an additional line of evidence, we analyse simulations from process-based fire models run under observed and counterfactual climate conditions, to estimate the expected effect of climate change on burned area in the region. These models suggest that the potential burned area in December-January in the Los Angeles area is today substantially higher than it would be in the absence of climate change. We note that these models represent changes in potential burned area driven by climate change but do not faithfully reproduce observed trends in burned area, and any real-world changes are the combined result of climate change and direct human interventions in the landscape.

The Coastal Southern California region is a small area, often represented by only a few grid-boxes in climate models and gridded observational products. Furthermore, the complexity of the weather conditions characterising fire weather and large year to year variability in rainfall means that precise numbers in every single line of evidence are uncertain. However, the lines of evidence examined overall point in the same direction, indicating that conditions that make extreme fires more likely are increasing. This is also in line with existing literature, as summarised by the IPCC (AR6 WGI, Chapter 12), that shows an increase in high temperatures, combined with a drying in the larger area and thus higher fire risk. Given all these lines of evidence we have high confidence that human-induced climate change, primarily driven by the burning of fossil fuels, increased the likelihood of the devastating LA fires.

The elderly, people living with disability (especially limited mobility), lower-income people without personal vehicles, and population groups that received late warnings were disproportionately impacted, as they had a more difficult time getting to safety. The neighborhood of Altadena with a large Black population was in the path of the fires, which destroyed the major source of generational wealth for many residents who had previously faced discriminatory redlining practices.

The wildfires exposed critical weaknesses in the city’s water infrastructure, designed for routine fires rather than the extreme demands of large-scale fires. The crisis highlighted the need for strategic investments in resilient water systems and improved pressure management, alongside stronger climate adaptation and emergency preparedness measures to address more frequent future wildfires.

The full study can be accessed HERE

Research by JAMSTEC may also shed some light on the weather affecting California

There is a pattern called the California Nino/Nina. Learn More about this HERE

And here is the recent JAMSTEC forecast for this pattern.

It shows a tendency for a positive California Nino which is really a totally different pattern than the traditional ENSO Cycle. Might it have had an impact on the wildfire situation? I have not spent enough time to try to figure it out but it is something to consider.

Disclaimer

Nothing in this EconCurrents newsletter is financial, investment, legal, or any other type of professional advice. Anything provided in any newsletter is for informational purposes only and is not meant to be an endorsement of any type of activity or any particular market or product.